Science for Science Sake

Like great works of art, there was no ‘reason’ for certain scientific endeavours, but this ‘just for the sake of it’ philosophy is now delivering tangible benefits.

Everyone is no doubt familiar with the phrase ‘Art for Art’s Sake’, coined in the early 1800s in France and taken to mean that the creation of art needs no purpose or objective, other than simply existing. I think we can all recognise that even the greatest artistic creations, from the Mona Lisa to Beethoven’s Fifth, didn’t need to be created, but humanity can be pleased that they were.

The question is, could the same be said about science? I would maintain that not only could it be said, but that we are doing humanity a disservice by not saying it often and forcefully enough. This is especially true in the modern context of science denial and bogus conspiracy theories, which gain traction partly due to a suspicion of the pursuit of science and its motives. It can be seen often in throwaway comments such as “what was the point of going to the moon?”, when in fact, even a cursory internet search reveals that so many of the things we take for granted these days, from cordless tools to fabrics and protective gear, were given a huge helping hand by the driving forces behind the NASA missions.

My own personal anecdote about pursuing science ‘just for the sake of it’ encapsulates perfectly the benefits that such a philosophy can bring to the world.

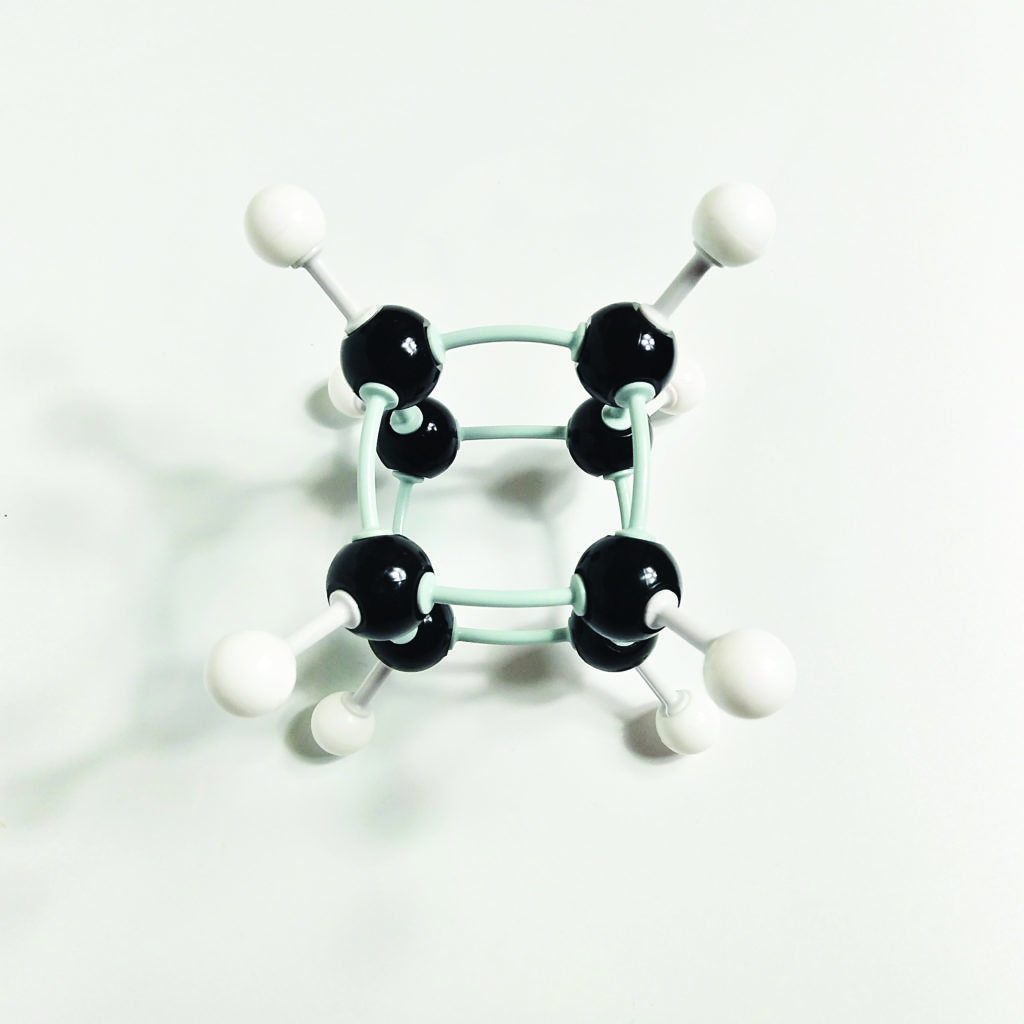

In the mid-70s, during the final year of my chemistry degree, I was captivated by a lecture in which the professor demonstrated how he had contributed to the development of a new molecule called cubane. Without going into detailed chemistry, it was the synthesis of a molecule which could never occur in nature – literally a cube of carbon atoms with the formula C8H8.

Everyone assumed it would be impossible to create such a molecule because the angles of the bonds between the carbon atoms would be too acute and make it inherently unstable, even if it could be achieved. But to everyone’s surprise, when it was finally synthesised, it proved to be remarkably stable and, perhaps more importantly, benign and non-toxic.

At the end of the lecture, I clearly remember the professor saying that it had all been a bit of fun and they couldn’t really see any use for it. I sincerely hope that he lived long enough to at least see the early fruits of his labours, because cubane, in true ‘science for science sake’ fashion, is proving to be something of a revelation, with applications from the military (sad but inevitable) through to materials science and pharmaceuticals. First, the bad news. We are all familiar with TNT – a high explosive which is essentially a benzene ring (toluene to be exact) with three nitro groups replacing three of the hydrogen atoms. That confers on the molecule a huge explosive potential. Crudely, explosives can be thought of as ‘unstable’ molecules being desperate to transform into more stable ones. So TNT turns into three very stable gases: carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide and nitrogen. Bang! It’s that simple.

Going back to cubane, someone had the bright idea of replacing all those eight hydrogen atoms at each corner with eight nitro groups. Octanonitrocubane (ONC for short) can convert into eight molecules of CO2 and four molecules of N2 with an explosive force that makes TNT seem like a popping balloon. Seriously deadly in the wrong hands.

More optimistically, cubane holds vast potential in materials science. Because it is a rigid, 3D structure, it can be layered or chained together to make amazing new translucent materials that could have applications in so many other science and technology disciplines.

But to my mind, cubane’s greatest potential lies in the field of pharmaceuticals and medicine. Again, it’s all down to its unique geometry and non-toxicity. The eight corners allow it to carry pharmaceutically active yet different molecules into the body, molecules that couldn’t otherwise co-exist. It’s still early days, but cubanebased pharmaceuticals are already showing promise in HIV and cancer.

So there you have it: the inspiration for first synthesising cubane was no more than a whim: “I wonder if it could be done.” Genuine science for science sake. Now, over half a century later, the world of science and technology is waking up to the wonders of this little cube of carbon atoms. To me that’s every bit as satisfying as listening to Beethoven’s Fifth.